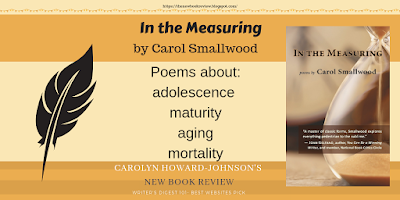

Title: In the Measuring

by Carol Smallwood

Publisher: Shanti Arts

August 2018, Paperback:120 pages,

ISBN: 978-1-947067-38-7

$17.00

Reviewed by Judith Skillman, originally for Compulsive Reader

Carol Smallwood’s language is exuberant as she threads themes of childhood, adolescence, maturity, aging, and mortality through the seventy-seven poems of her new collection, In the Measuring. Using free verse as well as formal, she examines seasons, myths, childhood, nature, and the plethora of experiences we encounter in everyday life.

Mysteries arise for Smallwood as she examines the ordinary. Under her microscope, something as everyday as a carwash changes suddenly to a cornfield: “Driving home, the corn that’d emerged in spring in such/straight emerald lines paraded in crumpled gold.” (“Today,” p. 34). Here, memory illuminates a landscape one generally equates with winter: “…–it was windy,/bags and newspapers flying the streets.” Through her wielding of the microscopic lens, a stray moment of recall provides not only a blast of color, but also a dose of nostalgia.

The saying goes: “the devil is in the details”; for Smallwood, however, one may say “the angel is in the details”. Whether it is a person, a landscape or a thing, concrete images accrue and become more than the sum of their parts.

For instance, in “Falling Leaves” (p. 36), the change of season from summer to fall creates nuances of feeling—in this case, of exile—which are echoed by new developments that have sprung up in a familiar locale. We have experienced this in contemporary life; it’s become normative and expected. For the witness in this poem, the tree losing its leaves becomes a metaphor for abrupt and continual change:

Nearby stands one tree

with fallen leaves crumpled

by sea change without

having seen the sea

Bringing the sea inland and giving the tree permission to “be” sensory without anthropomorphizing it is an angelic act, given the harsh details that “swirl” through this short piece.

The aforementioned exuberance comes with the author’s novel treatment of the everyday—those ordinary, mundane tasks and chores we take for granted. Who would think to write a pantoum about dishwashing liquid? Yet Smallwood carries it off, and braids colloquial language with scientific. She assumes a persona the reader can identify with:

There are so many on the shelves but had to select one —

antibacterial, concentrated, degreaser, biodegradable:

how bad were phosphates (what did they do) in the long run?

Surely an experienced housekeeper should be capable.(“A Dishwashing Liquid Pantoum”)

In addition to glancing aslant at a world overfull with choices,In the Measuringreveals the journey of an open-minded life-long learner and an ironic soul, one who wanders lightly through days and years. The line of questioning follows an all too familiar path we all tread—that of the mortal whose days and years are numbered. Through many modes of assessment, and myriad daily problems to be solved (even the mundane filling out of a questionnaire at the dentist (“Waiting for the Dental Hygienist” p. 84) standard communications become wholly inadequate.

As the adventure unfolds, this explorer searching for a way to properly interpret, label, and explain the world in scientific terms learns lessons she passes on to the reader:

How much knowing is good for us to know?

Venus, the admired morning star, is a sulfuric hell.

Know Thyself can be a Medusa turn-to-stone blow:…(“Knowing”, 70)

When examining the role of childhood myths, from Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, to the Wizard of Oz, Smallwood waxes feminist: “Sleeping Beauty/was awakened by the prince./What would’ve happened if/she hadn’t been a beauty?” (79)

The overwhelming amount of information that must be processed more and more quickly in our contemporary world cannot be reduced—that is no longer an option. Reading Smallwood, however, is not only possible but advisable. She herself is an avid reader. Perhaps the best we can do to insulate ourselves from the inevitable intrusion of overload is to opt in to one of Smallwood’s worlds. An ideal example can be found in one of her vignettes, a four-line poem emblematic of the whole:

I’m a child again

wanting to read

darkened tree bark

like Braille (“On Days of Slow Rain”, 96)

As a wanderer, this female Don Quixote struggles until, as a compulsive searcher, she finds a way to lower the bar and arrive at home under her own terms. That is, she comes to grips with the impossibility of finding a proper answer to unanswerable questions. She turns from shadows cast by inanimate objects to actual living things, even if those things must be bugs:

“The Bug”/ “was on the post office floor so put it in my purse:…” (p. 100).

What a surprising move.

The persona then goes on to describe what this insect liked: “…Subway lettuce, drops of coke in the car;”—and brings the bug round to another angelic moment: “It had survived countless species long extinct–/and if we wait, we may see the Spring”. Spring is capitalized intentionally here, for it is a Spring where the reader, who, we learn, lives between worlds (“I Read that Between,” 113) can hold winter and summer, and therefore light and darkness, at once.

MORE ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Judith Skillman’s recent books are Premise of Light, Tebot Bach; and Came Home to Winter, Deerbrook Editions. She is the recipient of grants from Artist Trust and from the Academy of American Poets. Her work has appeared in Shenandoah, Poetry, Cimarron Review, The Southern Review, and other journals. Visit www.judithskillman.com

MORE ABOUT THIS BLOG AND GETTING REVIEWS

The New Book Review is blogged by Carolyn Howard-Johnson, author of the multi award-winning HowToDoItFrugally series of books for writers. Of particular interest to readers of this blog is her most recent How to Get Great Book Reviews Frugally and Ethically (http://bit.ly/GreatBkReviews ) that covers 325 jam-packed pages covering everithing from Amazon vine to writing reviews for profit and promotion. Reviewers will have a special interest in the chapter on how to make reviewing pay, either as way to market their own books or as a career path--ethically!

The New Book Review is blogged by Carolyn Howard-Johnson, author of the multi award-winning HowToDoItFrugally series of books for writers. Of particular interest to readers of this blog is her most recent How to Get Great Book Reviews Frugally and Ethically (http://bit.ly/GreatBkReviews ) that covers 325 jam-packed pages covering everithing from Amazon vine to writing reviews for profit and promotion. Reviewers will have a special interest in the chapter on how to make reviewing pay, either as way to market their own books or as a career path--ethically!

This blog is a free service offered to those who want to encourage the reading of books they love. That includes authors who want to share their favorite reviews, reviewers who'd like to see their reviews get more exposure, and readers who want to shout out praise of books they've read. Please see submission guidelines on the left of this page. Reviews and essays are indexed by genre, reviewer names, and review sites. Writers will find the search engine handy for gleaning the names of small publishers. Find other writer-related blogs at Sharing with Writers and The Frugal, Smart and Tuned-In Editor.

The New Book Review is blogged by Carolyn Howard-Johnson, author of the multi award-winning HowToDoItFrugally series of books for writers. Of particular interest to readers of this blog is her most recent How to Get Great Book Reviews Frugally and Ethically (http://bit.ly/GreatBkReviews ) that covers 325 jam-packed pages covering everything from Amazon Vine to writing reviews for profit and promotion. Reviewers will have a special interest in the chapter on how to make reviewing pay, either as way to market their own books or as a career path--ethically!

The New Book Review is blogged by Carolyn Howard-Johnson, author of the multi award-winning HowToDoItFrugally series of books for writers. Of particular interest to readers of this blog is her most recent How to Get Great Book Reviews Frugally and Ethically (http://bit.ly/GreatBkReviews ) that covers 325 jam-packed pages covering everything from Amazon Vine to writing reviews for profit and promotion. Reviewers will have a special interest in the chapter on how to make reviewing pay, either as way to market their own books or as a career path--ethically!